· 7 min read

Where does this grid come from anyway?

Before going into the details, the conversation at the Museum of the City of NY starts with a quick overlook at the Greatest grid website that was made out of the 2011-12 exhibit of the same name. No need to describe this awesome source of information, just go have a look! Dive into the history of our city through beautiful maps, before safely guarded by the city and now available online after digitalisation. Namely, don’t miss the 1811 commissionner map of NY, where you can explore what has been preserved/altered over time ; and the Randel map, so precise and detailed.

But this event is about the book written by Gerard Koeppel: City on a grid, How New York became New York. The conversation is masterly led by architectural historian Hilary Ballon, herself author of The Greatest Grid, the Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011. It is a long and complicated story but both the author and the host made it pretty clear to us all, presenting two major maps, and their authors, that took a dramatic role in the shaping of NYC.

But this event is about the book written by Gerard Koeppel: City on a grid, How New York became New York. The conversation is masterly led by architectural historian Hilary Ballon, herself author of The Greatest Grid, the Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-2011. It is a long and complicated story but both the author and the host made it pretty clear to us all, presenting two major maps, and their authors, that took a dramatic role in the shaping of NYC.

1796, Map of Common Land, by Casimir Goerck.

At a time when the most valuable parts of NY are riverfronts, because they are the only access to the island, the city owns a number of properties in the inner (hilly) part of the island and wants to make money out of it. It commissions Goerck to design a plan to sell plots. He came up with 3 North-South avenues, 900’ apart; and a number of transversal West-East streets, 200’ apart; forming 5 acre blocks; dos that ring a bell to our New-Yorker readers? He designed what served as a model for the grid we know, which is more or less an expanded version of his plan. The 1811 Commissioners plan is indeed based on this Common Land plan, as we will see. What is to note here is how Goerck already envisioned an urban environment in the midst of the agricultural conditions of the time.

The Mangin-Goerck Plan, 1803

In 1797, Joseph François Mangin is famous for various maps and surveys in the NY area. Even Hamilton knows him! Beyond mapping, he designed the first prison of NY, located at Christopher St, “up the river”. In 1797 he got a contract with NY to map the city. But soon he wrote: I am not making a map of the city as it is but as it shall be. A draft was released in 1799, and the Council loved it! In 1803 the map was officially presented on a huge print. It is composed of part of the existing city, slightly idealized (some streets are wider, some blocks are filled out), plus segments of different rectangular grids stacked together. Those sections of grids vary in density and orientation, adapting to the landscape, aligning with natural features, and creating public interstices between the different grids. The success was complete and copies of the map started to be sold.

Until the street commissioner, Joseph Browne, who happens to be Aaron Burr’s brother-in-law, used his full power to trash the map down in 9 months and reject the plan, apparently for personal reasons: Burr is not a big fan of Mangin, as he sponsored his competitor, expected winner but defeated English designer, for the 1802 City Hall competition…

The grid, 1811

But still, even if Mangin’s map was put out of the picture by street commissioner, city representatives realized that having a plan for urban development was a good idea anyway. Full authority was given to a commission to come up with a new plan from 1807 to 1811. Three State commissioners, among with and eventually led by Gouverneur Morris, entered the act and had to overcome private owners fiercely fighting the city to keep their land. From what I understood, it looks like those three guys have not been working very hard on the map. In 1810, the Erie Canal commission took them away for a while. But in 1811 a plan had to go out. So, short on time, they simply took Goerck’s idea and expanded it to the whole island of Manhattan, up to 155th street.

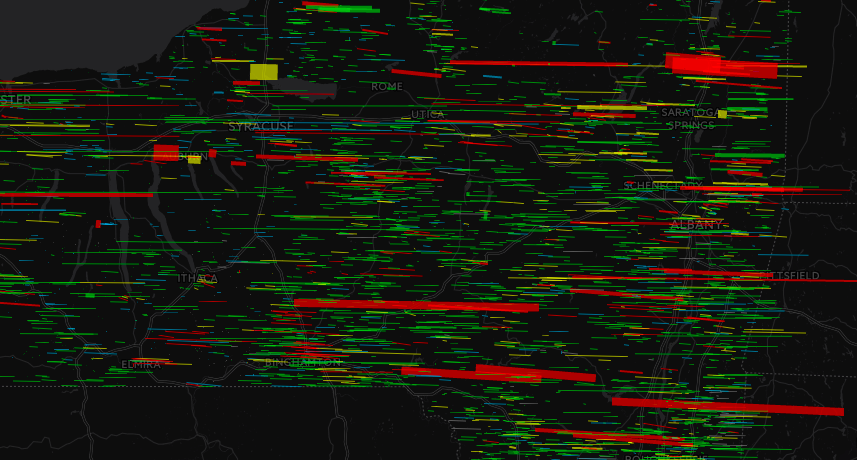

A plan is one thing, a city is an other. John Randel Jr, surveyor, was employed in 1811 to draw the map first and then to make it happen. As first implementation, he started with a precise survey of the existing, overlapped with what was planned. We can see how big the changes involved were, moving, trimming, cropping properties owned by hundreds of people. Property lines were all over the place, mostly farmland. And the process of buying properties was very cumbersome. Owners tried to sue the city but all lost, because the commission was legally empowered to do whatever it took to make the plan happen. What was the simplest solution on paper ended up as a plan very difficult to implement. It is the first time that a piece of land is bought to build public good. It already raised the question of how far can the State go?

But soon, with a rapid urban development supported by a clear plan, the land value skyrocketed, and objectors soon became hard supporters of the plan. This is how the grid eventually happened.

Mr. Bridges did a color version of Randal’s plan and sold many copies of it, getting easy credit for the plan.

Mr. Bridges did a color version of Randal’s plan and sold many copies of it, getting easy credit for the plan.

To the pros and cons of the grid

It is not rare to call an event a “conversation” but it is far less common to actually end up with a real conversation, between two people, with different points of view, sharing, listening, arguing. But this is - for once! - a real conversation between Gerard Koeppel and Hilary Ballon, who seem to disagree with each other about the (dis)advantages of the grid itself.

The author reads a number of quotes from other personalities describing the grid of NYC as a vast penitentiary, a thing impossible to overpraise, the most courageous act of prevision of the occidental world, an everlasting expression of expansion, the worst city plan of the modern cities, a spatial precision that is not accompanied with emotional exactitude (Sartre), and so on. But as the historian points out, other qualities emerge from the grid; like power and magnificence, qualities that are not recognized as such, like beauty, in an European sense. To the relationship between the grid and the power NY endorsed, it is a egg-and-chicken question. The efficient spatial mechanism in place either caused or supported a strong economic development.

The diagonal streets, like Broadway, were added later. They support a more efficient way to get to your destination, but the squared grid enables different ways to get to the same place. About the transportation system attached to the grid, its straight lines are inviting cars. Indeed public transportation is more developed in Boston, where crooked streets get easily traffic-jammed. There is no inherent conflict between a grid plan and sustainability though.

At first, the grid ended at 155th St, where the topography becomes too strong to be affordable to flatten it down. The later developments, such as Central Park, definitely marked up a new mindset. As for the late development of the grid, when the plan got filled, developers had no other way to build than go up. The verticality of the grid is very powerful.

There are a few “mistakes” in the NYC grid and the numbering of streets, for which we don’t really have any explanation. The grid of NY soon became a model for the rest of the country, namely because it applied even more easily on most American cities.

There is one virtue the grid has that no one can argue with: you never get lost! And what a better way for us immigrants to feel at home, than always knowing where you are and how to get where you want to go?!

Many thanks to Gerard Koeppel for his comments on this post.